"In the Silver Wildernesses":

Arno Rafael Minkkinen's Walkabout

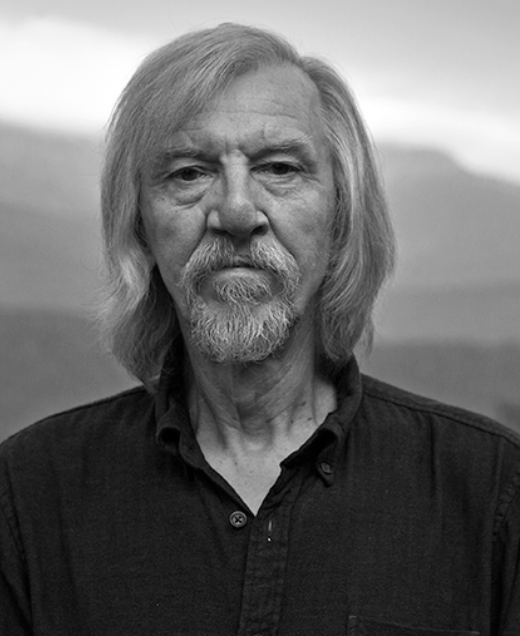

by A. D. Coleman

On September 2, 1971, on the outskirts of Millerton, New York, the Finnish-American photographer Arno Rafael Minkkinen began making images of himself unclothed — and never stopped.

Though he describes the initial impulse to do so as a response to a particular image by Diane Arbus, this connection seems oblique at best, its explanatory value obscure. That germinal image of himself reflected in an old mirror lying on a patch of grass in no way resembles the Arbus picture that sparked it. Nor does it look like any other images he would likely have encountered up till then. At the time, Minkkinen, a writer of advertising copy with an avocational interest in photography, had little grounding in the medium. Perhaps that freed him from certain strictures, because in 1971 neither contemporary photography nor contemporary art — territories that then overlapped only slightly — had any established place for someone of either gender who produced only photographic male nudes, or for a man who photographed himself exclusively.

That concept was not yet even a gleam in the eye of John Coplans, for example, whose own photographic activity (surely influenced by Minkkinen's work, as comparison of their respective images and the dates thereof demonstrates) would not commence till years later. Yet something was in the air, inarguably. Minkkinen's early works (along with those of others like Lee Friedlander and Lucas Samaras) heralded the arrival in photography and what we now call "photo-based art" of a specific aspect of the autobiographical mode in photography — the use of self as subject.

Minkkinen does not seem to have set forth deliberately to carve out a territory separate from that of anyone else. He simply gave himself a specific set of ground rules and stuck to them. He would use only the rigorous photographic techniques of the U.S. version of high-modernist photography: no double exposures, no darkroom interventions. He would investigate the actual physical surface of his own body, literally head to toe. He would generate pictures about that body as a scape in itself, and also about its expressive and communicative visual potential when interactive with the material world. Corpus as diegesis — his corporeal self as the connective thread for a body of work.

Of course, as Arthur Danto points out, Minkkinen couldn't have anticipated what lay ahead of him when he shed his garments and framed his image that day. Yet the seed of what would constitute a life's work got planted at the instant he allowed that ancient light to strike his body, bounce off that mirror, and register itself on his film by tarnishing the particles of silver suspended in its emulsion. In that fraction of a second Arno Rafael Minkkinen stepped forever into what The Kalevala, Finland's epic, calls "the silver wildernesses."

Shortly after making that picture, at the outset of his serious activity in the medium, Minkkinen elected to pass through what one would have to consider one of the educational hothouses of high modernism in photography: the graduate photography program at the Rhode Island School of Design, where Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind led the faculty, which he entered in 1972 at the age of 27 and left two years later with an M.F.A. His thesis portfolio, "White Underpants," appears in retrospect as a deliberate prelude to the subsequent undertaking.

Aside from a devotion to the gelatin-silver print as an interpretive vehicle for his imagery, what Minkkinen took from those two teachers and others with whom he studied included a commitment to the individual photograph as an autonomous utterance; an understanding of its potential role as a component of a larger statement; an acceptance of the rhythm and pace involved in the slow, patient, accretive construction of a durable body of work; and a deep engagement with what the late Walter Chappell called "camera vision" — an awareness of the transformative aspect of photographic seeing, the translative consequences of registering on film whatever appears before a lens.

Minkkinen's working method clearly derives from those internalized precepts. Occasionally he uses friends and family as participants in his pictures, but in every other sense he always works alone: like Samaras, but unlike Coplans, he involves no assistants in the production of his pictures. He scouts and decides on the site or locale; he sets up the camera and frames the view; he performs the depicted action unaided; he chooses the moment of exposure and releases the shutter. He does not subject the consequent images to digital revision or darkroom alteration; what they depict actually took place before the lens. He makes his own prints. All this may (indeed, should) affect the way one understands his pictures.

Minkkinen is self-defined as a photographer — not a performance artist, or a conceptual artist, or a maker of "body art" or "photo-based art," or an "artist using photography," Yet wherever he locates himself in that regard, the substantial project that he initiated shortly before the advent of postmodernism and has sustained through the present pertains to many of the movements and issues of contemporary art and photography, among them performance art and body art, the construction of identity, and the male nude. Clearly it relates in various ways to the use of self as subject, model, or both that would come afterwards in the work of Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Francesca Woodman, Tseng Kwong Chi, and others. No less obviously, it has analogues in the activities of such diverse contemporaries as Andy Goldsworthy, Ian Hamilton Finlay, and Dieter Appelt — each of whom has initiated transient events that endure primarily through the photographic documentation thereof.

However, Minkkinen hasn't made his photographs merely to annotate and inform the viewer about these adventures of his as such. His priorities flow in the other direction: He's performed these acts for the purpose of generating potent images. Elegant, witty, inventive, and often stunningly beautiful, the pictures he creates in these circumstances stand first and foremost as acts of visual creativity. This perhaps provides the strongest evidence and signification of his roots in photography. Otherwise, while his work emerges in some ways out of the field of ideas of photography, it's hardly typical of that visual discourse. Its closest precursor is probably Alfred Stieglitz's cumulative "portrait" of Georgia O'Keeffe, the first true Cubist work in photography: an open-ended series of observations of an individual, seen from different perspectives and made over an extended period of time, gradually layering or collaging themselves into a many-faceted whole.

In any case, identifying his own lean, angular, agile, unclothed form as the primary subject and locus of his creative activity, Minkkinen has since 1971 traveled throughout the U.S, western and eastern Europe, Japan, and the Nordic countries. During these decades he has steadily generated astonishing and memorable pictures. Though he has made notable images in historic cities — among them Paris, Prague, and Helsinki, the city of his birth — as well as inside his own home, Minkkinen mostly stages these events for his camera in and around natural, even elemental settings: forests, lakes, rivers, mountains, deserts, canyons, oceans, fields of ice. He has buried himself in snowdrifts, hung from ski lifts, submerged himself under rapids, dangled over precipices — and simply dipped his fingers into shallow water. So, regardless of how one approaches and positions them, in aggregate these photographs form an astonishing account of one man's primal engagement with the civilized and natural worlds, and with himself — both a physical odyssey and a psychological voyage of the solitary human spirit.

Since the mid-1970s, Arno Rafael Minkkinen has exhibited and published widely throughout the world. He has issued three previous major monographs, and his prints have entered the collections of numerous museums and other institutions. Recognized in Europe and Japan as one of the major figures in contemporary photography, considered a contemporary and peer of Duane Michals, Ralph Gibson, and others, he is curiously less familiar to U.S. audiences. Thus this survey takes on two challenges: that of introducing to those who come to it for the first time Minkkinen's work in its full scope, organized so as to make its underlying concerns and deep structures apparent; and that of presenting it anew to those who have followed it for years, in such a way as to reveal the breadth and sweep of this unique long-term enterprise. Saga, the most extensive examination of Minkkinen's oeuvre to date, distills 35 years of his efforts, clarifying such matters as its autobiographical aspect, its pantheistic ritual component, its cross-cultural underpinnings, and its documentation of this artist's demanding and often hazardous actions in the pursuit of his images.

Saga is a retrospective exhibition of Minkkinen's work since 1970, curated by this author with Todd Brandow of the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography, with an accompanying book-length catalogue. Both versions of this survey share the same selection of pictures and organizational schema. As curators and editors, we have configured this 120-print selection from Minkkinen's body of work as a long, unified visual poem. In constructing it we have brought together an unprecedented mix of his already iconic, immediately identifiable pictures, numerous lesser-known pieces, and previously unpublished and unexhibited photographs — including a generous sampling of images produced from 2000 to the present. More than one-third of these works appear here for the first time.

Among other things, these pictures, taken as a whole, record a journey of epic duration and distance, as well as a series of tests of courage and endurance — the very essence of the Nordic literary form known as the saga, from which this retrospective takes its title. Because Minkkinen remains deeply identified with his Nordic roots, and especially his Finnish heritage, this exhibition draws on the Finnish national epic, The Kalevala, as an intermittent, elliptical, and fleeting reference point. This long poem influenced the photographer deeply from his childhood onward. Saga does not constitute an illustrated version of Elias Lönnrot's distinctive compilation of interlocking tales and spells (which in any event remains known to few outside of Finland). Instead, Saga serves as an independent, bardic telling of the life story of its idiosyncratic doppelgänger, the fictional character Arthur Danto dubs "Arno," in which appropriated, bricolaged fragments of The Kalevala enhance the sense of narrative flow and mythopoeic environment.

That fragile, deliberately illusory story line sustains the weight of this experiment in extended form, while also functioning here as an organizing principle for Minkkinen's imagery. Yet the reading of Minkkinen's project that this sequence proposes — as an ongoing vision quest — stems organically, even inevitably, from the work itself. In actual fact, Minkkinen has for three and a half decades engaged in his own persistent version of a seemingly perpetual "walkabout," and the images bear eloquent witness to this restless seeking. Given the self-evidently purposeful nature of his wanderlust, we might then consider his pictures as equivalent to Australian Aboriginal "dreamtime" paintings, a process not of staking out territory or claiming it in any proprietary way but instead of psychically "mapping" in images the complexly layered physical and spiritual dimensions of the land, a means of establishing what Bruce Chatwin tells us those "first people" think of as the world's "songlines."

In the course of these voyages Minkkinen has returned again and again to certain prosceniums: assorted natural environments, European cities with deep historical and cultural resonances, situations in which female friends can serve as protagonists, and his own home and family. Rather than arranging his images chronologically, or grouping them according to their specific geographic locales, we have clustered them topographically and thematically. Pulling these diverse creative acts together into homogeneous suites lets us see how, over the years, he has explored each of these recurrent theatrical stages as imaginative fields of play and springboards for picture-making.

Assembling those clusters as chapters of the skeletal quasi-narrative of Saga seemed also to arise from a logic inherent in this body of work. Minkkinen's long-term project meets all the conditions of epic-scale quest: travel to distant and exotic places; the exploration of unfamiliar territory; deeds of strength and valor; the enduring of long stretches of solitude; the imperative of mission or purpose, even if unarticulated. Plus, as motive, the process of coming to terms with a wound both psychic and literal. Given all that, arranging the topographic and thematic clusters just described sequentially, as installments of a panorama of emergence, search, ordeal, and arrival home, seemed less the imposition of an infrastructure on Minkkinen's work than a way of inviting the viewer of that work along for the ride.

There are, in fact, at least three intertwined narratives in Minkkinen's work generally and in Saga specifically with which one can engage. You are welcome to follow any or all of them.

First, you have of course the chronicle of Danto's "Arno," that eccentric fictional character who exists only in these photographs, a changeling whose peregrinations, travails, exploits, camouflages, and self-exposures as he wends his way slowly homeward enchant the viewer. Meanwhile, en route, taking his time, whether off in the wild or invisible to any eyes but your own in populous cities, this heroic oddball treats the world as his playground, one long chain of monkey bars. He even behaves that way in the house, setting a terrible example for the children. (Doesn't that look like fun?) Better warn them not to let you catch them trying any of these stunts.

Second, there is the engrossing and often breathtaking physicality of that personage whom Danto names "Minkkinen," the model for these pictures, and his acrobatic performance for this photographer's camera and film, unparalleled in the medium's history — a set of actions that position him somewhere between athlete, contortionist, daredevil, and dancer. (How did he do that?) Alan Lightman has written about Minkkinen's evocation through his pictures of what I would call a kinaesthetic empathy; what this effects, if one gives oneself over to these images on that level, is an imaginary workout both exhausting and exhilarating, as one moves with him vicariously through these images.

Third, one can choose to track the photographer Arno Rafael Minkkinen's creative visual play with the potential inherent in the interaction between various environments, his physical form, and his lens, camera, and film: the continuous, startling shifts of perspective and variations of point of view; the surgical precision and formal intelligence of his framing; his prescient attunement to what his tools and materials will make of what he points them at; his mastery of the printmaker's craft; his ceaselessly inventive use of the external world and his own body as raw stuff from which to generate a continuous, never-repeating stream of indelible pictures.

But there is a fourth dimension to this work, a plane on which that character's multiplicity of personae, the model's impossible agility and grace, and the photographer's concerns as artist and craftsman merge with the communicative purposes of a man, a storyteller, who would speak to us through them about himself and his life. A rich complexity of thought, emotion, and mood runs like a river within this body of work. Despair, grief, anger, fear, solitude, loneliness, and a deep inwardness all make their appearances here — as do revelation, humor, exuberance, playfulness, celebration, ecstasy, generosity, and love. Above all, an endless delight over the privilege of existence in the moment, and in the world. If the dominant note of Arno Rafael Minkkinen's work is one of transcendence, or what Arthur Danto describes as "lightness," it is not a juvenile or frivolous state of mind but an adult's earned, courageous, and mature achievement, a purposeful balancing of darkness with light, a triumph of levitas over gravitas that acknowledges and honors both.

© Copyright 2005 by A. D. Coleman. All rights reserved. By permission of the author and Image/World Syndication Services,

在银盐的荒漠——阿诺·拉菲尔·闵奇恩的徒步旅行

1971年9月2日,在纽约的米勒顿郊区,芬兰裔美国摄影师阿诺·拉菲尔·闵奇恩开始了人体自拍创作,并从此再未停止过。

闵奇恩并没有故意去阐明自己开创了一个与任何人都不相同的摄影领域,他给自己一系列特定的基本规则,并且坚守它们。他只使用美国版极端现代主义摄影中严格的摄影技术----没有双重曝光,不做暗房调整。他详细的观察他自身人体的真实身体表面, 从头到脚逐一进行。当他的身体与物质世界相互交融的时候,他拍成的照片只是把身体在自身作为景色,展现他身体的表现力与潜在的视觉交流。肢体作为时空连续统一体的叙事----他的躯体本身成为这个人体作品的连结线。

闵奇恩根本没能预料从他脱掉自己的外套,把自己拍入画面的那一天起,会有什么问题摆在他的面前。在他让老窗户的光线照在他身上的那刻,能构建一生事业的种子就被播种下了。光线经过镜子的反射,让悬浮在感光乳剂中的银粒子失去光泽,将自己身体记录在胶片上。从那几分之一秒开始,他永久地踏入了名为"银盐的荒野"的芬兰史诗----卡勒瓦拉(The Kalevala)。

除了热衷于使用乳胶基银盐照片作为表达其影像的载体, 闵奇恩从他的两位主要导师哈里•卡拉汉和阿伦•西斯金德以及其他老师身上学到了: 对自治表达方式的独立个人影像的信奉;对作为相对大的陈述单元中的一个构成部分的潜在角色功能的理解; 对和缓慢、耐心、共生表达方式相关的持久人体作品的韵律和步调的认同;对最近被Walter Chappel 称为 "相机视觉"(一种可变化的视点的摄影的看的意识)的身体力行。

闵奇恩不是行为艺术家,不是概念派艺术家,不是"人体艺术"或"光影艺术"的制造者,也不是以摄影为手段的艺术家,作为摄影师闵奇恩有自己的界定。他在后现代主义出现前不久开始这个课题并且一直持续到现在这个拥有行为艺术、人体艺术、身份解构、男性裸体等运动和议题的大氛围。然而无论在什么情况下他在这个充实的摄影课题中去定位自己,他的做法很明显和别的一些把自身作为主题或者模特或者两者兼而有之的各种方式相关。这些方式都在诸如Cindy Sherman、Robert Mapplethorpe、Francesca Woodman、曾广智等人的作品之中有体现。同样明显的是,他和形形色色的同侪在行为上有相似之处,例如Andy Goldsworthy、Ian Hamilton Finlay and Dieter Appelt,他们每个人都发动了长久载入摄影史册的瞬态事件。

然而,闵奇恩没有仅仅以其这样的敢作敢为来吸引观看者和给他的摄影做注脚。他优先考虑的是:他所做的这些是为了拍摄有影响力的影像,优雅的,设计巧妙的,有创造性的,并且常常伴有让人震惊的美丽,他在这样的情况下拍摄的图片最首要的是作为一种视觉的创造力。这也许是他的摄影根基的最有力的证据和特点。除此之外,他的作品显现出超出摄影观念领域之外的独特性。最近的先驱也许就是摄影师Alfred Stieglitz拍摄的现代女画家Georgia O'Keeffe的系列"人像"。这是第一批真正的立体主义摄影作品:一个没有框架限制的个体观察系列,从不同的视角观看,并且伴有时间的延续性,渐渐的经过分层或拼接成为一个多面的整体。

在任何情况下,他将简洁,瘦削,敏捷和裸露的形体定为他的主题,并且注重了他的创造行为。闵奇恩从1971年开始旅行,遍及美国、欧洲的东西部、日本和北欧国家。在许多历史名城他拍摄了值得关注的影像,例如巴黎、布拉格和赫尔辛基---他的出生地,闵奇恩几乎是为了他的相机和周围的自然而拍摄的,甚至是自然的基本元素:森林、湖泊、河流、山脉、沙漠、峡谷、海洋、冰岛。作为总体,这些图片的产生有令人惊讶的理由----一个男人关于文明与自然世界最初的信奉,还有他自己精神上长期探索和一个孤独人类灵魂心理的旅程。

这些图片作为一个整体,记录了一个史诗般的长期远距离旅程,也是一系列对于勇气和耐心的测试---像人们知道的北欧传说英雄萨迦(SAGA)。将闵奇恩的作品作为正在进行的视觉探索来品读是很自然而然的,甚至是不可避免的 。事实上,闵奇恩35年坚持不懈地从事看上去永无休止的"徒步旅行"的视觉工作。 这些图像留下了永不停息的探索过程中强有力的见证。 考虑到他自身的旅行癖,我们可以认为他的图片等价于澳大利亚土著的"黄金时代"油画。这不是一个立界圈地或以任何所有权的方式来宣称的过程,取而代之的是一种精神上将复杂多层的土地的物理和心理尺寸在图像上的"映射", 就像布鲁斯·查特文所告诉我们的那些"第一批人"如何看待"歌之版图"。

在旅行的过程中,闵奇恩一次又一次地回归:各种自然界的环境和有深厚历史文化背景的欧洲文化城市,以他的家人和女性朋友为主体的创作对象。完成这个史诗般的长远计划需要各种各样的条件:要到那些没有人烟的荒芜之所,没有被开拓的蛮荒之地,需要具备力量和勇气,忍受长时间的孤独,还要清晰认识达到这些目标的条件,甚至还有各种未知的因素。需要指出的是,这些过程中无疑有对精神和心理上的伤害。

在他的作品中,至少有三个紧密相连的故事可以让人感兴趣:

第一,你可以在作品本身中体悟到作者传奇的人生经历,体验他的漫游历程,艰辛的心境,开拓精神,伪装和自我暴露,他极具诗意的回归创作使观看者入迷。

第二,作品中的躯体引人注目甚至使人窒息,镜头前他杂技演员般的行为,在艺术表现方式上是空前的,一系列的动作把他置身于运动员、柔术演员、蛮勇的人和舞者之间,闵奇恩通过他的作品唤醒了我,我称之为"运动感觉共鸣"。

第三,观看者可以通过照片中不同环境,身体形态,作者相机、镜头和胶片,这些信息来探寻摄影师创造性视觉行为的足迹:他让自然原始的肢体与外部世界相融合,不停地进行创作拍摄,持续不断且永不重复。

但是,他的作品还有第四个特点,一个人物多样性的表现形式,在作品中表现出一个模特不可思议的机敏和优美,作为艺术家,一个男人抱着交流的目的来讲故事,通过图片向我们介绍他自己和他的生活。这些复杂的思想、感情和情绪像河流一般流淌在他的艺术中,绝望、悲伤、愤怒、恐惧、孤独、寂寞和深深的内心世界,让他们在这里一一展现出来。启示、怪诞、丰富、趣味、狂欢、迷幻、包容,还有爱。尤其重要的一点是,在这一刻,这个世界上,无限的欢乐已经超越了特权的出现,如果阿诺·拉菲尔·闵奇恩的作品是一次超越,他这不是幼稚和轻佻的想法,是一个成年人应得的,英勇而完美的成功,像黑暗中的光芒,是超越名利之外的非凡成功所带来的喜悦。